- Hush-money prosecutors say their "entire case" rests on an obscure NY election conspiracy law.

- Attorneys specializing in state election law believe the statute has never been prosecuted.

- But two election law scholars said DA Alvin Bragg's novel strategy may well get Trump convicted.

At Donald Trump's hush money trial on Tuesday, a Manhattan prosecutor surprised law nerds in the audience by revealing that "the entire case" rests on a single section of New York's election law.

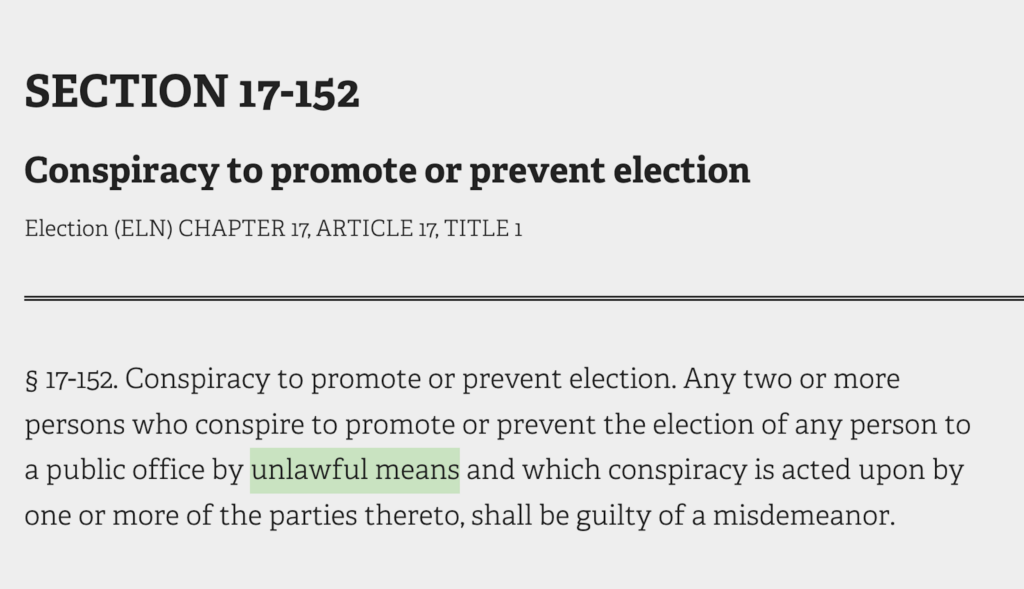

The statute is simple. It outlaws conspiring to promote or prevent someone's election through "unlawful means."

Trump is on trial for falsifying business records throughout his first year in office to hide an election-influencing hush-money payment to porn star Stormy Daniels.

Falsifying business records is a misdemeanor, but the charge becomes a felony — punishable by up to four years in prison — if the records were falsified with the intent to commit or hide some other underlying crime.

Now, Manhattan prosecutors now say an old, rarely used section of the state election law is their favorite on the menu of potential underlying crimes.

"As the court is aware, falsifying business records in the first degree requires an intent to commit or conceal another crime," prosecutor Joshua Steinglass told New York State Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan on Tuesday.

"The primary crime that we have alleged is New York state election law section 17-152," Steinglass told the judge, lifting into prominence an arcane measure that had previously played only a supporting role in the case.

"There is conspiracy language in the statute," the prosecutor said, "The entire case is predicated on the idea that there was a conspiracy to influence the election in 2016."

Business Insider asked two veteran New York election-law attorneys — one a Republican, the other a Democrat — about the law, also known as "Conspiracy to promote or prevent election."

Neither one could recall a single time when it had been prosecuted.

"I've never heard of it actually being used, and I've practiced election law for 53 years," Brooklyn attorney and former Democratic NY state Sen. Martin Connor said of section 17-152.

"I would be shocked — really shocked — if you could find anybody who can give you an example where this section was prosecuted," agreed Joseph T. Burns, attorney for the Erie County Republican Committee in Buffalo, New York.

"I would be absolutely floored," Burns continued, "if you could find anyone prosecuting this in the last 40 years."

Two highly respected law professors specializing in New York election law said the same.

Neither could cite a time when 17-152 — a misdemeanor that's been on the state's election law books since at least the mid-1970s — had been used.

However, while the two attorneys were highly skeptical of the DA's newly focused strategy, the two election law professors told BI they were confident it would lead to a conviction.

Sure, 17-152 has never been used before, they said. But that doesn't mean it won't work now that the dust has been blown off.

"I think it's very smart of prosecutors to use this state law, whether it's been used before or not," said Jeffrey M. Wice, who teaches state election law at New York Law School.

Wice noted that two judges — Merchan and Judge Alvin K. Hellerstein, a Manhattan federal judge who rejected Trump's attempt to move the hush-money case to federal court — upheld the use of 17-152 in this case.

"It's a solid statute and very straightforward," Wice said. "Just as we have to expect the unexpected from Donald Trump, we have to also expect the unexpected from prosecutors and the jury."

An underlying crime

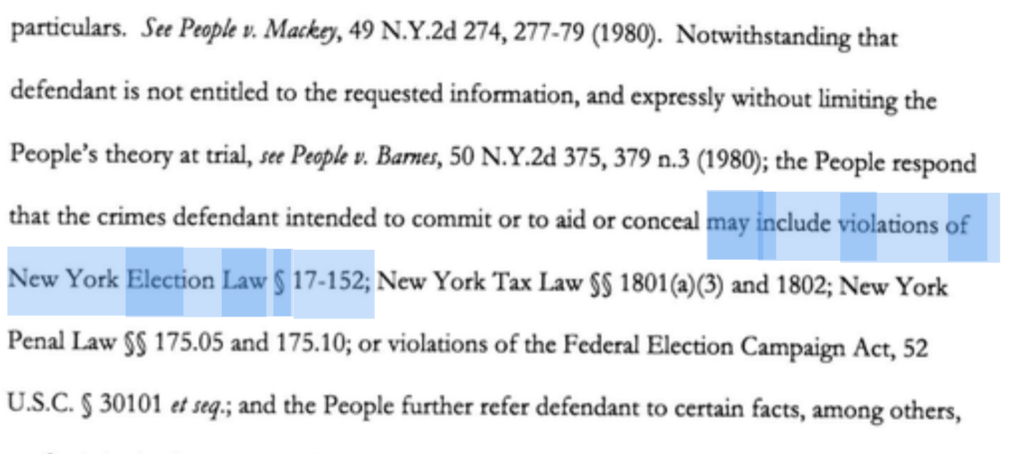

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg first mentioned New York's election conspiracy law nearly a year ago in a May 2023 filing called a bill of particulars.

It was mentioned only in passing.

The underlying crimes — either committed or merely intended to be committed — that hoist Trump's falsifying business records up from misdemeanor to felony "may include violations of New York Election Law section 17-152," prosecutors wrote.

In the same bill of particulars, prosecutors said the underlying crime could also be an intent to violate state tax law because Trump's then-"fixer," Michael Cohen, paid Daniels $130,000 out of his own pocket. Trump hid the true nature of that outlay when he reimbursed Cohen through a series of monthly checks for "legal fees," money Cohen then claimed as income, prosecutors say.

As an alternative, the underlying crime could be an intent to violate federal election law, prosecutors said, under the theory that the hush-money payment was an illegally high campaign contribution.

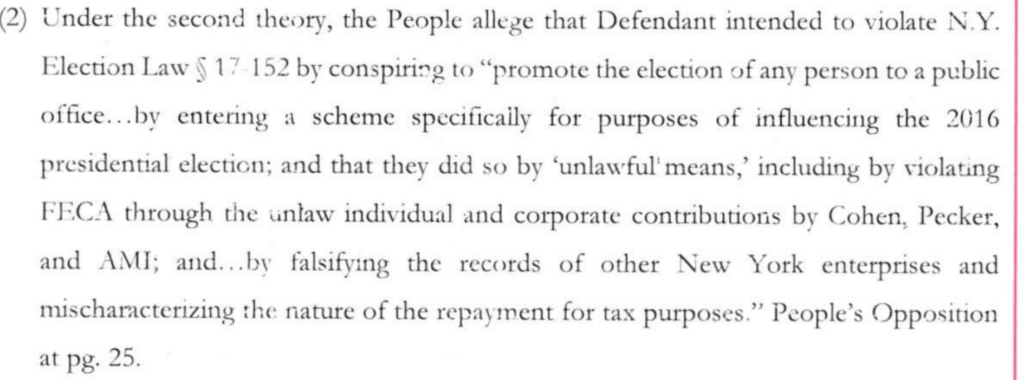

These same three "underlying crimes" — using state election law, federal election law, and state tax law — were again given equal prominence here in a February 15 decision by Merchan.

Only on Tuesday, when Steinglass spoke to the judge, did section 17-152 take its starring role.

Crimes, within crimes, within crimes

Connor, the former state senator and longtime election law practitioner, said there's a problem with letting 17-152 do the heavy lifting in the Trump indictment.

Falsifying business records requires proof of at least an attempt to commit an underlying crime to be a felony.

But what if that underlying crime is section 17-152 — conspiring to mess with an election through "unlawful means?"

Things will get "twisty," Connor said, when prosecutors try to show that Trump's falsified business records are felonies because of an underlying crime — 17-152 — that itself needs proof of a conspiracy to do something "unlawful."

"You're having an underlying crime within an underlying crime to get to that felony," Connor told BI.

"It's novel," he said with a laugh. "It's novel," he repeated.

Section 17-152 needs its own underlying criminal conspiracy, he said.

"Two or more conspiring to elect or defeat a candidate — that's the definition of every political campaign," he joked. "It's only when you conspire to do it by unlawful means that you violate this law."

Having an election-conspiracy statute like 17-152 on the state election-law books makes little sense, he said.

"It would appear to cover something like three people getting together and saying, 'Let's break into our opponent's headquarters and destroy all his equipment,'" Connor said.

"Or, 'Let's firebomb the place.' There probably have been cases like that, but for that kind of illegal conduct, you would use the state penal code and charge arson or burglary, which are felonies," he added

"Because if you're only using this election law, you only have a misdemeanor."

Winning isn't as tricky as it sounds

What will prosecutors argue made Trump's 17-152 election conspiracy "unlawful?"

They've already cited three ways.

First, there's federal election law. Prosecutors have alleged that the conspiracy intended to violate the Federal Election Campaign Act, or FECA, which sets strict limits on contributions.

Trump conspired with Cohen and editors at the National Enquirer to bury Daniels' story of a 2006 one-night-stand — long denied by Trump — by paying her $130,000, prosecutors say. That money was an illegally high campaign expenditure, they say.

Second, Trump intended to violate state tax law when he disguised his repayment of Cohen as a series of monthly checks for "legal fees," prosecutors say.

And third, Trump conspired to falsify the records of the National Enquirer through a plan to "catch and kill" stories that could hurt his 2016 campaign, prosecutors allege.

Proof of an intent to violate any of these three laws would be sufficient to satisfy Section 17-152. And once you prove 17-152, you have the underlying crime you need to raise misdemeanor falsifying business records to a felony.

It's important to remember that Trump is only charged with 34 counts of this one crime: felony falsification of business records, said election-law scholar Jerry H. Goldfeder.

Trump is not charged with actually committing any of the underlying state and federal laws required to prove felony falsification.

So prosecutors have no legal obligation to prove he's guilty of any of these underlying laws, 17-152 included, said Goldfeder, senior counsel at Cozen O'Connor and author of Goldfeder's Modern Election Law.

"They only have to prove he intended to commit these underlying crimes," which is a far lower bar, said Goldfeder, who also directs the Fordham Law School Voting Rights and Democracy Project.

"I think it's a very viable case," he told BI.

"And the testimony so far demonstrates that Trump intended to pursue this catch-and-kill scheme and to falsify business records to cover it up — and did so to influence the election," he said.

"It's up to the jury of course," he added. "But the testimony so far is pretty clear."